|

Lens × Block World as Construction Kit by Jay Saul Silver 3. Contributions In part 1 of this section I will talk about the virtues of lenses and blocks, neither of which has the virtues of the other. In the second section I will talk about combining the virtues of both into a single object. Finally, I will provide one method for thinking about and improving existing Construction Kits so that they have the dual lens-block advantage. I’ll go into detailed specifics with the example of a painting kit. I will also define Constructive Lens. Lenses, take magnifying glasses for example, are an amazing tool for inquiry. The entire visible world becomes something worthy of inspection, maybe even investigation, to a curious individual augmented with the use of a magnifying glass. Of course the whole world was already “willing” to be investigated, but the addition of the particular tool, by design, enhances the possibility of the particular action of investigation. Blocks on the other hand, take wooden blocks for example, are an interesting tool for architectural creation, tinkering, reconfiguring a known set of parts. A person augmented with the power of wooden blocks is a person who is highly likely to create towers, maybe even towns, etc. Wooden blocks are great for rearranging. Wooden blocks invite anyone from 1 month to 100 years old to put their hands into the action and start creating and destroying in cycles. But blocks are not a very good “lens” onto all the parts of the world. That is to say, playing with wooden blocks rarely teaches about ladybugs (or fingerprints or table salt). What about magnifying glasses? How likely are they to lead to experience with creation, experience with repurposing? How often do lenses lead to a reordering of the physical world? It doesn’t happen by design, though it may happen by accident. So, when thought of as a tool for education, a wooden block is, by design, made to teach about creative action, and a magnifying glass is, by design, made to encourage investigation of the world. What if we put them both together? Many educators would agree that both lenses and blocks are great ways of learning. And so they are often employed... separately. But what is it that happens when you combine the two into a tightly coupled pair? I call this a Constructive Lens. What does a “Constructive Lens” do? One interpretation is that when you tightly couple the acts of creation and exploration (wooden blocks and magnifying glasses) you get people investigating the properties of the everyday world (like a magnifying glass) and you get people reconfiguring and tinkering (like wooden blocks), and that when you do them at the same time, you might get people engaged in the process of re-investigating and reconfiguring the everyday world in tightly coupled iterations. This “Constructive Lens” is 2 things at once. It is a lens, because it is a world view. At the same time it is a way of acting because the world view enables an activity of appropriation and designation of meaning. The Constructive Lens inherently diminishes the strength of the idea that there is only one existing order in the world simply by bringing to light the possible existence of infinitely many possible orders.

While a high bar indeed, creating a situation in which people take objects from the everyday world, analyze the objects’ properties so as to re-see their workings, and then synthesize something new by combining the objects together or casting newly designated purpose on their use, is an exciting prospect. This means that people are re-seeing the world as repurposable, thinking of it as malleable, and acting in accordance. Another way to say this is that the Constructive Lens will encourage the process of repurposing the world, thus creating the space for the thought that the world is malleable, and seeing the world in accordance. The two statements are one in the same. If there is a Constructive Lens that works this way, one might even say the actions taken by the person using it bestow a confidence and sense of agency, create a fertile ground for expression, and even a sense of empowerment. There are many modern Construction Kits, such as: paint sets or electronics kits. Modern Construction Kits often come in a box with everything you need so that you can get started right away creating. There are many genres and subgenres of Construction Kits within various fixed media. For any expressive medium (gardening, sculpting, 3d printing, computer programming) one can imagine the design of several kits to support the activity. For a given kit, is there a way to open up the box a bit so that the kit leads not only to creative action within the confines of the kit parts, but so that the kit also becomes a sort of lens onto the world as potential creative pieces or as a potential creative space? Let’s define Construction Kit, not for the purposes of an absolute taxonomy, but for the purposes of scaffolding the generative process of turning kits inside out so that they become lenses onto the world (while still being kits for creative action). Let’s say that Construction Kits have 3 components: 1) Parts (especially loose parts) 2) Tools (for combining and reconfiguring loose parts) 3) Stage (a substrate or place where the creative action is situated and may live on) (note: not all kits will have all 3 parts, and not all kits have to fit nicely into this framework) A strategy for turning a “regular” Construction Kit into a “World as Construction Kit” situation might be to choose one component of the kit and remove it from the kit. Instead the creator must look to the everyday environment to find that component. Assuming the construction kit is expressive enough, then the user is motivated to make something with the kit, but by removing one of the components of the kit, some of that motivation to express is directed toward the everyday world as the user now goes on a sort of hunt for what they can use. In this way, the user is directed toward the everyday world and begins looking around with an eye for “how can I use this item for such and such a purpose” as they scan the environment looking from thing to thing. Take a painting kit for example. It might consist of: 1) Paint (loose part) 2) Brush (tool) 3) Canvas (stage) But what if there is no paint? Perhaps the creator can be encouraged to scavenge paint from crushed berries, or from objects (like rainbow sprinkles or small pebbles) mixed with glue. In this scenario, if the creators eye scans across a berry (or a balloon, or some cheerios, or a blade of grass, etc.), the creator asks herself, “How could I see this berry (or cheerios etc.) as if it were paint?” Then, having had experience with berries (or cheerios etc.) the idea of using it as paint either snaps into place or doesn’t or somewhere in between. The creator is catalyzed to reconsider the usages of their everyday world in particularly constrained ways, like “How could this be used as paint?” In doing so, the creator has to strip out the normal meaning of what they think they know, “This is a berry, berries are for eating,” then hold that berry, now stripped of its supposed “known” purpose, in a new light, a light of paintability. (Cheerios, by the way make a great, albeit chunky style, paint when combined with glue). What if there is no brush? Perhaps the idea could arise to boil spaghetti and paint with it, or grab a toy race car and use its four wheels as brushes while driving the car around the canvas, or stamp leaf patterns. In this scenario, the creator once again has her attention directed toward the everyday world to reconsider what she thinks she knows about common objects. As she scans her couch pillows, her cat’s tail, a light bulb, and a gallon of milk, each is considered as if it were a paintbrush, and what it would mean to think of each object as a paintbrush. This is the “Constructive Lens” effect: to look at what we already know and consider it for new uses, consider its properties and affordances, and how those affordances might be beneficial, interesting, or surprising in a new context, different from the originally designated or generally agreed upon purpose. What if there is no canvas? This seems to point to the field of graffiti or sand dollar art. Buildings or sea creatures become the canvas. In this scenario, the creator gets to reconsider objects as a medium that carries a painted picture or holds paint as a substrate. What does it mean to paint a picture on a car vs. a building vs. painting directly on water? Is that even possible? How? What would happen next? Can you paint on air? On rain? Can you paint on a rainbow? What about the head of a pin? What about on human skin or bones or a flower or a porcupine? While these types of questions could be asked and practiced as an exercise in and of themselves, it is so much more powerful and meaningful to engage with them in the context of an expressive project in which these questions are an inherent part. The point is not to prove that any of these art genres are particularly new, though I think it’s rare that people try to paint pictures on porcupines, but rather to evoke the idea that perhaps this framework is a generative way to think of new media art and even new types of Construction Kits that are Constructive Lenses onto the world: A kit that catalyzes querying everyday objects for their paint-properties and then using those objects as paint to create an expression, is a kind of Constructive Lens for “World as Paint.” Let’s reconsider the same paint kit, but in the additional light of digital tools:

Table 3.1. Construction Kit Components Concretized Through a Particular Painting Kit Example As described earlier, I/O Brush [Ryokai +, Computer Human Interaction 2004, I/O Brush: Drawing with Everyday Objects as Ink]. is a digital brush system in which paint is sampled from the everyday world around you. When using I/O brush, you can’t even start until you take a picture of something with the brush (“sampling a digital paint swatch from the world”). There is no color picker in the program. You simply have to look to the world and touch the brush to something to get the texture and color of an object in your environment so you can begin painting. Not only do you “have to” do this, but it is quite exciting and expressive to take the texture of an eyeball and begin to make a drawing out of it. Once that desire is created, the desire to look around and see the texture and color of everyday objects as useful or not useful for the painting you wish to create, then in the human mind a sort of “lens” forms when looking around at things. The lens is not literal, but instead is a way of seeing. Specifically it’s a way of seeing the world for its component parts, in this case color and texture, and how those component parts could be used to make something, in this case a painting. This is a specific type of inquiry that is not inquiry into the working of machinery, but specifically inquiry into what can be created out of the everyday world. A sort of creative inquiry. The person starts to see the World as Paint or more generically World as Loose Part, which is a form of World as Construction Kit. Glowdoodle (Rosenbaum, Creativity and Cognition 2009, Glowdoodle: A Medium for Expressive Inquiry) is one example of a light-drawing system in which everyday objects can be used as paintbrushes. It allows you to wave objects in front of the webcam and trails of those objects appear on the screen if they reflect or emit light or color. The creator thinks, “What kind of a resulting brush stroke will this LED toy (or this smartphone screen, or this sunflower) have when waived across the scene?” The creator imagines each item, or perhaps tries without imagining too much, depending on the person, as a digital brush. In doing so the person starts to break down the world into types of object reflectance and light emission, even if not explicitly thought of with that vocabulary, to evaluate the usefulness of each T-Shirt, paper airplane, and Starburst wrapper as digital paint brushes. The person starts to see the world as paintbrush (or more generically, world as tool). The L.A.S.E.R. Tag project [Graffiti Research Lab, 2006, L.A.S.E.R. Tag] is a digital graffiti system that encourages you to look around the world and consider any solid object as a potential canvas for drawing on digitally. What if I laser graffiti on the moon? What about a foggy night? What about my body as a canvas for laser graffiti? The lens of digital graffiti, like the lens of old fashioned graffiti, is a lens in the mind of the creator that makes the creator look to the environment with an eye for “How would it be meaningful to transform this item by painting on it?” “How will this item take to the digital ‘paint’ based on its properties?” “What is this tube of toothpaste as a canvas for laser graffiti? What about this waterfall?” The person begins to see the World as Canvas (or more generically, world as substrate or world as container). Whether of the form new media art or traditional crafting, separating a construction kit out into its component parts and then systematically removing a component and asking “what if we direct the user’s attention to scavenging that component from the world?” can be a way to generate new “World as Construction Kits.” Ultimately, “World as Construction Kit” is a state of mind that represents a world view. II. Design 4. Constructive Lenses in the World This section will start by taking a traditional kit, and “opening” it to explore the specific differences between a Constructive Lens and a traditional construction kit. Then we will try to define what is different specifically and give terms to those differences. Finally, we’ll take a look at Constructive Lenses that already exist in the world. Open LEGO -- Opening a Traditional Construction Kit What if some traditional LEGO kits came with a special set of LEGO bricks that were made just for attaching to other objects around them? Ideally there would be a few LEGO bricks that could attach to each type of material in both the man-made and natural environments. Imagine the following “Open LEGO” scenarios: ● Suction LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks with a suction cup for attaching to very smooth surfaces like glass or polished materials “When I was done making the birdhouse I suction cupped it to the outside of my window, and a real family of birds moved in” ● Eyelet LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks with an eyelet so that it can have string looped through it to be tied to things “I made a beautiful flower bud, and when I was done I looped it through my necklace chain and wore it as a pendant. Afterwards, I started a tradition of decorating the tree in the front yard with my LEGO creations” ● Floatation LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks with floatation built in so that objects can be built on liquid surfaces “I built a mini rowboat and put a ladybug inside it to pretend she was lost out at sea. We attached the row boat to a LEGO floatation platform and pushed it into the pond, and we elaborated sagas of the misadventures when the wind would blow it this way or that...” ● Snap-In LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks with velcro, button holes, or snaps so that they could attach to other objects that have those receivers “I’ve been playing hacky sack for a while, and I thought that it would be great to have a little ‘scooper’ on the top of my velcro shoes, so I built one and attached it with the velcro LEGO piece. I’ve been modifying my design each day after hacky sacking.” ● Sticky LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks with very sticky tape for attaching to somewhat smooth surfaces like weathered wood or rusting metal, or leaves “I am making a little teepee out of sticks and leaves, and I wanted to add some windows, so I used the tapable LEGO to help hold my windows in place and bind it to the sticks.” ● Magnet LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks with magnets to attach to fridges or other toys that contain magnets “I like to make marble machines out of LEGO bricks, and I stick the machines to my fridge with magnets which makes them easy to move around and reposition. The ‘marbles’ are metal ball bearings, so I can also use the magnet pieces to alter the course of the ball bearing. When I play in the bathtub, my marble machine becomes a water machine, because I noticed that bathtubs are magnetic too. Sometimes I build with my LEGO set and my magnet kit at the same time because they are inter-operable.” ● Other Kit LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks that have little attachments for Tinker Toys, compatible K’nex hookups, and 3 sizes of holes to press-fit twigs. “Today I gathered up some fallen branches, and I made a dome on my tree fort with a hybrid of K’nex, LEGO bricks, and twigs.” ● Visual Media LEGO -- Some LEGO bricks with a clear plastic pouch that can hold a printed or drawn image on one side and can be drawn on with markers or pencil on the other side. “I made a mask in the shape of a gator and then drew teeth and scales on with a pencil.”

and on and on like this.....

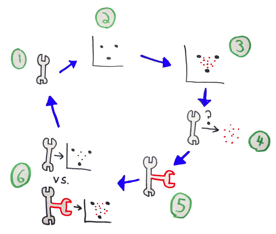

LEGO bricks as they are now can and always have been repurposed and combined in all kinds of situations, but it has been despite, not because of, their design. In this example the traditional LEGO construction kit is composed of different colored loose parts called LEGO bricks. Because the LEGO bricks are press fit (the fasteners are built into the top and bottom of each LEGO), there is no tool other than the human hands that are needed to perform the basic construction operation. LEGO kits often but not always come with a substrate in the form of a big LEGO sheet to attach your creation, and the design of this sheet is not generic or implicationless: it implies that the creation should sit on top of something flat, like on a floor, shelf, or table. In the example, we opened the loose parts of the construction kit with the “Other Kit LEGO” brick. We opened the substrate with the “Flotation LEGO” brick. In doing so we turn the LEGO kit into a lens onto the everyday world for considering how the LEGO kit might interact with and be co-constructed with the everyday world. Open Construction Kits What is Open?What do I mean by open? To open a construction kit is: To redesign a construction kit so that one of its components (parts, tools, or substrate) is left unspecified in a way that suggests it should be drawn from the world around you. I mean to operationalize the idea of “World as a ______.” For example, one way to “open the painting kit” is to “invite the artist to appropriate the properties of everyday objects as the paint” (as in I/O brush). A closed construction kit is one where the loose parts, tools, and substrate are fixed and unchangeable, at least by design (anything is changeable if you try hard enough). But something doesn’t sit right about that definition. Take a basic painting kit for example. It seems quite open ended, as we can paint pictures of anything even if it’s always with the same paint, brush, and canvas. There is one more piece to the puzzle of open activities using open construction kits. Take for example a typical construction process. There are some people who came to construct something: where did they come from and who compelled them to do so (Prologue)? There is some situation or theme, or goal in which the construction is carried out (Beginning). Then the materials are gathered and acted upon with tools (Middle), a final project is converged upon (End), and then that final project is placed somewhere (Epilogue). 1) Prologue - People: Recruitment mechanism, Theme, Setting 2) Beginning - Loose Materials 3) MIddle - Tools 4) End - Final Project crystalised 5) Epilogue - Placement or Afterlife of Project This is very rough because it ignores all the iterative loops and complex processes involved with creative action and activity conception. But it serves our purposes. The reason a normal painting kit seems so open-ended is because it is exactly that. The end product is completely open (unless there are instructions guiding otherwise). It’s only the loose parts (the beginning) and materials (the middle) and the substrate (the epilogue) that are closed. That is to say that traditional painting is open-ended (step number 4), close-beginninged (step 2), close-middled (step number 3), and close-epilogued (step number 5). That is, unless you are in a class where everyone is to paint the same subject, which it would be close-ended. Now in this case, of course, everyone’s painting will turn out a bit different, but this is not called open-ended. But the interesting thing is: what does it mean for a project to be open in a way other than open-ended? Let’s take painting as an example. If a painting project is open epilogued but closed elsewhere else, then one example would be: Everyone will start in the same room with a bowl of fruit on the table. Everyone will get a brush and a set of paint colors and a piece of paper with glue that is meant to be affixed to something in the world when completed. Everyone will paint the bowl of fruit on their canvas. Then when they are done they will go out into the world or into their house or onto their bodies and affix their painting somewhere. You might think of that project as open-ended as it is indeed a project with different outcomes. And that would be accurate. But the project idea was generated via thinking of it as open-epilogued, and that is the power of the technique of opening a component of a construction kit. Note again that open-epilogued painting projects often end up feeling like graffiti (or tattoo projects if affixed to a person’s body). Banksy, the most famous modern graffiti artist, does his graffiti in just that way: first create the art, then roll it out on to building street or facade. But tattoo is definitely distinct from graffiti in my mind. Importing and ExportingMany now accept that facts and knowledge alone are not a satisfactory outcome of an excellent learning process, and that we must “learn how to learn” or learn to “be creative.” To make creative space, many activities (including standard/basic LEGO construction in their older original form) are open ended. That is to say, at the end of playing with a basic LEGO set, each person will have a different finished product, if they have a product at all. (This isn’t always true of LEGO kits, as the majority of modern LEGO kits have prescribed building patterns, like a particular Star Wars spaceship). This “Open Endedness” is a form of open, and is much more likely to connect to something that the creator finds personally meaningful than if the end product is prescribed. What you see in the Open LEGO example above is a case for LEGO projects to be -- by design -- open-beginninged, open-middled, and open-epilogued.

Importing (or “open-beginninged” and “open-middled”)To the LEGO Company’s credit they have a nice concept of System and Play, which refers to the LEGO Company’s policy of making parts that mix and match among themselves using a standard protocol for connection. For LEGO sets to be open-middled, they need to be able to mix, match, and connect with the material world outside of the LEGO system, like in the Other Kit LEGO example. This type of combinability that provides an openness to the beginning or middle of the building process could be referred to as importing. Importing happens when the material world can be brought into the kit world to act on or be combined with the kit’s loose parts. Most modern art software applications allow the creator to import existing images into their work to remix, collage, or mashup.

Exporting (or “open-epilogued”)Floatation LEGO says to creators, “When you’re done building something, maybe you should take the final product and put it in some water.” Like importing, there is a certain connection that is being made to the creator’s everyday life. Another, perhaps more powerful, type of exporting is to share the finished product with friends. Since the advent of YouTube, the average video has had a much more vibrant epilogue to its creation story. The final video project can be uploaded to YouTube, which is probably already part of the creator’s everyday life, and then many types of social interactions can begin around the video. (Note: The document you’re reading was created with a word processing toolkit that allows for exporting to PDF for easier sharing). Importing and exporting is really just another way of talking about whether a given toolkit is interoperable with various parts of the world. There are formats, languages, protocols, and other ways of aligning with standards so that a toolkit can incorporate or be incorporated into different parts of everyday life. In the software world this is called “API” and is one of the most important aspects of a modern webified application. Beyond interchangeability, instructions and positioning have a big effect on whether something is exportable or importable. Permission changes the mindset. Some Existing Constructive Lenses Non-Digital Constructive Lenses Already in Existence Out in the World MakeDo MakeDo is a set of tools

Figure 4.1. MakeDo’s Overview of Parts. (Images reproduced from mymakedo.com)Parent Hacks says "Makedo hits the jackpot with early independence and open ended play." And it is true that it is open-ended, and it also happens to be open beginninged in that the materials which you use are not specified. Further it’s not completely open beginninged in that it has some suggestions and most of its examples focus on cardboard. However even cardboard comes from many sources and in many forms. Here is an example of how MakeDo would be used:

Figure 4.2. MakeDo’s four steps: Find, Create, Play, Share. (Images reproduced from www.mymakedo.com)Notice the attention to the beginning with an explicit attempt to encourage the bricolage and open beginninged-ness by showing what appears to be a random collection of junk all of which can be operated on using MakeDo. These instructional materials are key to support the open beginninged-ness and “World as Construction Kit-ness” of MakeDo. If the kit shipped with cardboard and didn’t encourage bricolage in the support materials and instructions, then despite its potential as an open construction kit, it may not realize its potential as such. Notice the attention to epilogue in the “Share” step. Though I wouldn’t say they have gone the extra step to encourage sharing in multiple substrates, I would say they stopped short of making the kit explicitly open epilogued. Note the language around “Play” and “Create”. While these are communicative and typical linguistic usages, they point to an important mistake in thinking about play patterns. The “create” step is extremely playful and just as an important part of true play as the “play” step. In unhindered child play patterns children will make, bend, and break the rules of the game and the physical components of the game all as part of the game play. This type of game play in fact develops the same part of the brain that is used in adult civic and family life for - Setting agendas - Stepping back and focusing in on project goals and ways of engaging with a project - Structuring relationships in group dynamics - Negotiating and deciding on goals and norms - Determining the very experiences that life will make up Edible Seed Bomb Kit

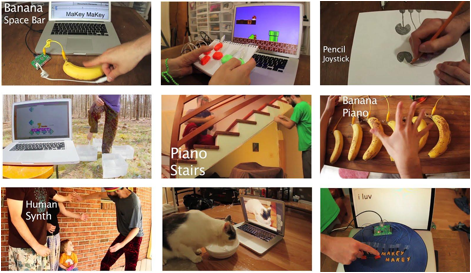

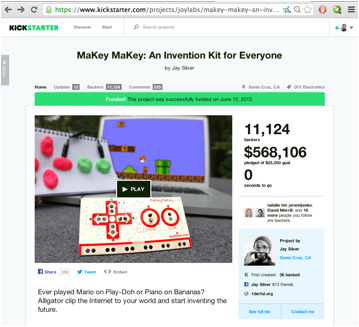

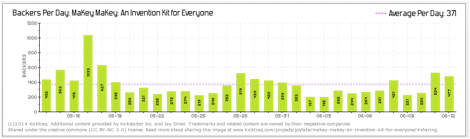

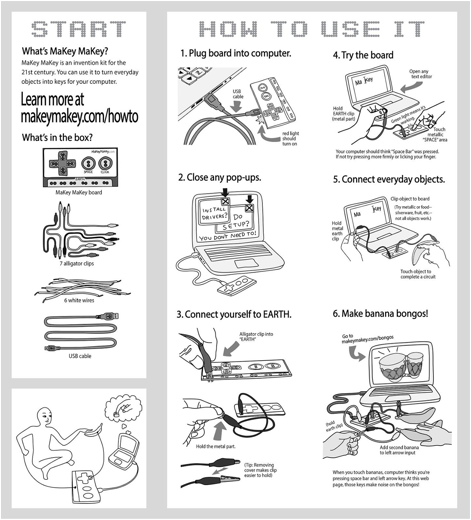

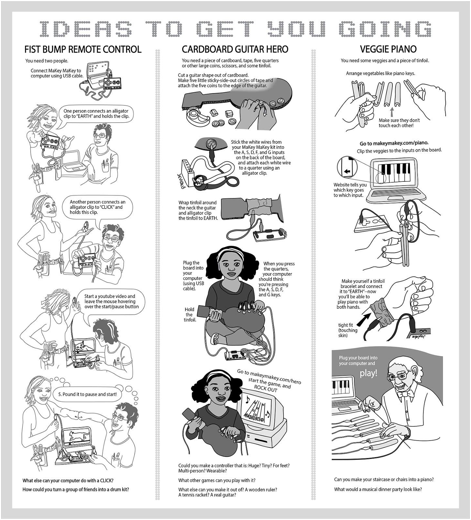

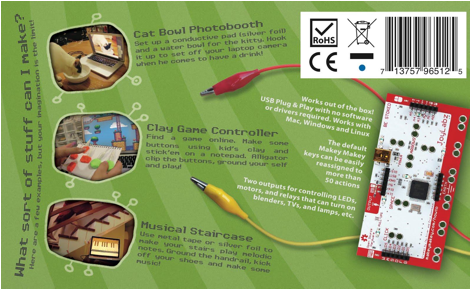

Figure 4.3. Edible Seed Bomb Kit Screenshot. Image reproduced from visualingual.comThis seed-bombing kit is closed-beginninged with the seeds already provided to you. The form factor is explicitly open-epilogued as it is a throwable ball with proteins for the seeds and the seeds inside the ball. The seeds are chosen just so that they will likely grow in a variety of climates and soil conditions thus making them explicitly useful for growing in multiple substrates, which makes their epilogue or “garden canvas” open. They are missing an opportunity to have been open-middled. Since they don’t provide any tools for launching the seed bombs into the world, they could have provided instructions that people should make or find tools or mechanisms by which to launch their seed bombs using strings, slingshots, ramps, cars and bikes, secret holes in pockets of pants, etc. While this kit has the potential to be open-middled, it missed the chance to operationalize that potential with some simple instructions or examples, making it less likely to happen, or at the very least making it implicit instead of an explicit design parameter. Interestingly, note that the epilogue could be considered split: open in the first half of the epilogue as to the substrate of where the garden grows, and then closed again in the second half where the kit suggests picking the edible plants and cooking them according to a recipe book. Using the “open construction kits” framework, the makers of this tool could consider whether their recipes could involve mixing in other ingredients that aren’t explicitly listed, or they could consider under what circumstances the dinners made with the recipes could be served, thus giving new chances for openness and creativity. The closedness of the second half of the epilogue of this kit is not problematic, it is good to have open and closed components of the kit. And it is good to be aware of these choices, as we live in a world that has lost balance with open parts of play. Digital Constructive Lenses co-created by Myself and Eric Rosenbaum● Twinkle [Silver & Rosenbaum, Tangible Embedded Interaction 2010, Twinkle: Programming with Color] Video at: TwinkleVid.notlong.com Compose 2D musical compositions with colored objects or colored markers. Then play them back by tracing them with a color sensor wand. Twinkle allows people to think of the world (objects with colors) as a musical composition, and rearrange that world to compose one’s own compositions. ● Singing Fingers [Rosenbaum & Silver, Interaction Design with Children 2010, Singing Fingers: Fingerpainting with Sound] Video at: SingingFingers.com A way of finger painting with sound, and then tracing the painting to get the sound back out as if scratching on a record. Singing Fingers uses a touch screen interface to convert sound into color and then back into sound again. Singing Fingers catalyzes people to think of the world (the sounds objects and voices can make) as paint and as components of a musical drawing. ● Color Code [Silver & Rosenbaum, Tangible Embedded Interaction 2010, Twinkle: Programming with Color] Video at: ColorCodeVid.notlong.com Color Code is a platformization of the concepts in Twinkle in that instead of producing sounds from colors, any computer action can be taken based on the color of an everyday object. In this way, everyday objects can be viewed as musical compositions, game controllers, or even computer instructions. Color Code catalyzes people to think of the world (the hues and shapes of objects) as components to interactive video games and interactive scenes. ● Drawdio [Silver, Creativity and Cognition 2009, Nature as interface: MacGyver'ing and Martha-Stewart'ing interactivity with trees, pencils, grandpa, even the kitchen sink] Video at: Drawdio.com A circuit that lets people hook up everyday objects to turn them into musical instruments. A simple 555 timer converts electrical resistance to audible sounds. (Note: There are several Drawdio products on the market, so when I say “Drawdio” in this thesis I am referring to what is commercially referred to as “Drawdio Fun Pack” which is a pre-soldered circuit with 2 alligator clips that is ready for the creator to start using to repurpose objects as soon as it comes out of the box.) Drawdio catalyzes people to think of the world (the analog electrical conductivity of an object between certain attachment points and the actuation of that conductivity by moving the objects through space) as a musical instrument. ● Makey Makey [Silver & Rosenbaum, Tangible Embedded Interaction 2012, Makey Makey: Improvising Tangible and Nature-Based User Interfaces] Video at: MakeyMakey.com Makey Makey is a digital-computation-platformization of the concepts in Drawdio in that instead of producing sounds from electrical resistance, any computer action can be taken based on the electrical resistance of an everyday object. Makey Makey lets you hook up everyday objects as if they were a keyboard or mouse to control software on your PC running in the OS or on the web. Makey Makey catalyzes people to think of the world (the digital conductive or insulative on/off connectedness of objects) as a user interface to a modern computer. For the purposes of going deep and making a clear point, the thesis will focus in particular on two tools, Drawdio and Makey Makey. These two tools will be covered in more depth in the next section since they are the focus of this thesis. 5. Drawdio Genesis This chapter and the next chapter approach the understanding of the Constructive Lens through a design exploration of two new Constructive Lenses. I (along with Eric Rosenbaum) have developed several tools which fit the pattern of what I have been calling a Constructive Lens, as mentioned in the last chapter. How did these come into being and what were the circumstances and influences? I will explore Drawdio in this chapter and Makey Makey in the next chapter as examples. As mentioned previously in Background, I had been working with the concepts of sensor inputs and actuator outputs and had decided to try to simplify the combinations to something less flexible to look for some more creative action. I was sent on a mission to Drishya, a slum school in India headed by Geetha Narayanan. Geetha had agreed with us that the goal for the visit would be nature sensing, which fit right in with my interests at the time. I stopped in Paris to join up with Evelyn, another member of the team, and there I spent some crucial time with Jean Baptiste LaBrune, who would later become a postdoc in the Media Lab. Jean Baptiste, also known as J.B., Evelyn, and I toured around Paris for a couple days thinking about nature and sensing. We visited some museums with green walls growing on the side of the building: a vertical living garden built into a building wall. We visited some hacker spaces and set up some sensor experiments there with PicoCrickets, Scratch, and the sensing of leaves and water. J.B. showed me two very interesting incarnations of a sensor-actuator pair which only 5 years later would I realize were influential. The pair was a solar panel and a piezo. If you hook a solar panel to a piezo, you can see the piezo vibrate and hear it buzz when enough light, especially direct sunlight, falls on the solar panel. J.B. incidentally showed me two things he has made with this combo: 1) A “robot” or “little figurine” with a solar panel on the chest and piezos incorporated in such a way that when light fell on the solar panel the little figurine would begin to move by vibrating and slowly “walking” ala vibrobot. Thus when placed near a window, as the sun traced out a patch of light on the ground throughout the day, the “robot” would walk out of the way of the sun patch because upon the sun patch falling on it, it would begin to move until no longer illuminated. 2) A stick the size of a broom handle with 5 solar panel / piezo pairs glued to it in a straight line. They all buzz intermittently depending on whether strong light is falling on each solar panel at that moment. And, if you twirl it around, especially near a window, the ambient light falls on different parts of the stick in different amounts in changing ways over time and interesting sound patterns emerge. I don’t know how much J.B. connects those two incarnations, or whether he knows they influenced my design in the future. I only recently become consciously aware of the connection when writing this thesis. I want to point out the importance of the experience in Paris with Evelyn and J.B. Evelyn played a very supportive artistic role of accepting my ideas unconditionally and riffing with me off them. J.B. played a role of expanding my ideas and making me think anything was possible as well as showing me around various environments and materials to make me think. This type of adventure-research and co-stoked-ness is important to making breakthroughs as it creates a safe and stimulated space to think big thoughts.

Figure 5.1. Study of plants as part of urban nature in Paris. Images in Figures 5.1 through 5.8 were taken interchangeably by myself and Jean-Baptiste Labrune.The left and middle show two sides of the same scene, a study of plants with a macro lens at a museum. On the right I am pondering a vertical green wall at a museum. The greenery behind me is actually the side of a building permeated completely with plants by an artist.

Figure 5.2. Left: Closeup study of the texture and composition of the non-living parts in various places sidewalk in Paris. Right: Study and consideration of a set of plants encaging a generator, then a set of metal bars encaging the plants, then that nested set of encagements forming a “C” shape with me inside partially encaged.During our study of the city’s cracks and crevices, and urban nature, we were intrigued to find plants in a cage, which upon investigation seemed to have been used to hide a generator, then the cage used to protect people from getting into the generator. Next, at a hacker space in Paris, using several sensor boards, we began to study some of the plant and nature samples

Figure 5.3. A Scratch Sensor board plugged in up front, with 3 other sensor boards behind it.

Figure 5.4. Scratch board with leaf measuring resistance; note early presence of bananas which later became important in Makey Makey.

Figure 5.5. The setup at the hackerspace. Lots of sensors, lots of crafts, and a room, with J.B., Evelyn, and myself.

Figure 5.6. The Scratch sensor board readout on a laptop.

Figure 5.7. Pouring water from one bin to another while measuring electrical resistance as a graph over time as shown on the screen in the background.

Figure 5.8. Evelyn playfully working, working playfully.In these images above you can see Evelyn, a previous grad student in Lifelong Kindergarten working on the sensors with us (right) being playful with the sensors (middle) and what happens when she finds a stage prop lobster claw in the middle of hacking (left). The reason I include the picture of the lobster claw attack is to show the mood during this phase of the exploration which was explosive and playful, like kids on an adventure. With these ideas fresh in my mind off we went to India (Evelyn and I). I, along with various collaborators on Geetha’s team, and members of Lifelong Kindergarten, were running Scratch workshops at a slum school in India called Drishya. Specifically we were focusing on nature sensors (water, plants, wind, sun, etc.) + Scratch. We showed the Drishya faculty and students some of the experiments we had done with the Scratch board and sensors that could measure nature.

Figure 5.9. Testing out the measurement of “nature” with Drishya facilitators using the Scratch sensor boardI was teaching myself how to solder and how to hack analog electronics. One day we were playing with PicoCrickets and had them hooked up to convert electrical resistance to sound. This was not the first time someone had hooked something up this way. But something was starting to emerge in watching the way these particular curious children reacted to “listening” to resistance, and here was a certain creative space opened up by my previous experiences with Camera for the Invisible plus the recent trip to Paris where we had worked with nature and sensors and urban exploration. Later that day we played with the PicoCricket as a resistance-to-sound input/output pair:

Figure 5.10. Left. Listening to the sound of the resistance of an apple with a PicoCricket. Right. PicoCricket resistance-to-sound measuring dirt.

Figure 5.11. Pico Cricket resistance-to-sound measuring rubber or plastic bicycle grip

Figure 5.12. PicoCricket resistance-to-sound measuring skin on headThat afternoon we went to Sadar Patrappa Road (S.P. Road) where all the electronics parts supplies stores are located. I bought a full electronics kit from 3 different stores including a hack saw, solderless and solder breadboards, resistor capacitor and potentiometer packs, LEDs, batteries, connectors and wires, and anything else you need to do basic electronics. Then we went to Om Electronics, shown on the map below:

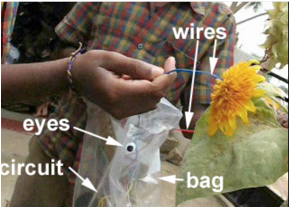

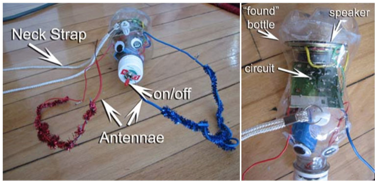

Figure 5.13. Where I bought the harmonium circuit is marked by a pin and the area around is where you can buy all sorts of electronics.Here they had several “kits” to follow instructions and build certain projects. I bought a heartbeat detector and a “Harmonium Circuit”, which was a piano circuit (harmonium is a more prominent version of a piano in India, although it is reed based). Back at home I started soldering. I worked into the night until about 3am. I had a stack of metal bowls as the mother of the family downstairs would bring me vegetarian meals in metallic bowls that stack on top of each other as is common in India. I didn’t have good lighting and I have bad eyes, but I did manage to get the harmonium circuit soldered and working (figure below). The circuit worked by connecting a metal wand from “ground” to any of a number of points along a resistor ladder. The higher in the ladder the more resistance was measured and thus the lower the pitch the harmonium circuit would make through its speaker. Each point in the resistor ladder was connected to a metallic pad that the wand could land on and connect the circuit. At one point I spilled the stack of metallic bowls on the kitchen table where I was soldering (note to future people: solder is toxic with lead, don’t solder on the kitchen table; I didn’t know this). Some dahl spilled out of one of the bowls and onto the circuit. Oh no! It started to make sounds and as I cleaned off the dahl the sounds changed. At first this seemed very curious, especially at 2am (with my roommate Evelyn sleeping in the room nearby too). Then I realized the sounds were being made by the dahl on the resistor ladder connecting the 555 timer to ground. As I wiped up the lentils, the resistance changed. Through some experimenting, I found out I could hold the metal wand in one hand and touch the pads with my other hand instead of touching the wand to the pads. Then I found out I could put the wand into the lentils and touch the lentils with my hand and touch the pads with my other hand and complete the circuit. I had an idea. I dumped out a water puddle on the table. I put the wand in it and connected to the pad and the puddle with a finger on each hand. As I moved my finger in the puddle I could hear the resistance in the circuit loop changing. I didn’t know what it all meant but it felt so fun and magical. I packed up the circuit into a ziplock bag I had been using to keep socks in from my suitcase. I put googly eyes on the bag to personify the circuit, and I soldered on two stripped solid core wires: one where the ground plane was and one coming off of one of the harmonium pads, and I poked them out from the bag so they were like two antennas for measuring resistance as sound (like a resistance input / pitched sound output pair). Yes, the PicoCrickets kit comes with pipe cleaners and googly eyes. I packed the mangled harmonium circuit into my backpack for the next day at summer camp / school.

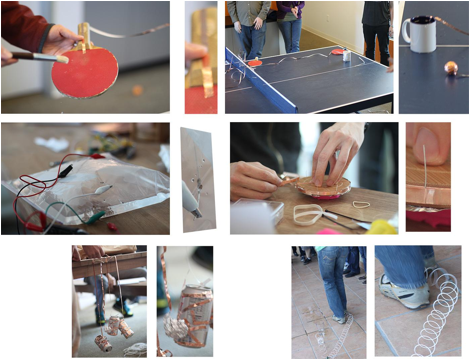

Figure 5.14. Harmonium Circuit in a plastic ziplock bag with wires poking out and googly eyes for personification. This is the best picture I have access to of the circuit in the ziplock bag. The 9V battery is in the bottom right corner. The speaker is touching it. The green rectangular circuit can mostly be seen partially obstructed by a Drishya student’s arm. The pads are silver rectangles.We took the circuit and poked the “antennae” into all sorts of things

Figure 5.15. Listening to the electrical resistance between two separate clay plant pots

Figure 5.16. Listening to the electrical resistance between two flower buds

Figure 5.17.Trying the circuit in a bag in all sorts of scenarios explained below.On the top you see two boys working together to listen to the resistance of a plant stem on the right, and to listen to the electrical connection between two separate pots of soil on the left. It was surprising to us that two separate pots would have an electrical path of conductance to each other. After experimenting with what became “Drawdio” over the next several years I learned that unpainted clay pots and concrete are water permeable and therefore conductive if some amount of moisture is present (unlike plastic pots and asphalt which are not). In the second row, you can see the kids testing different metallic objects: tea kettles, tea cups, and door handles. Touching the circuit wires to metal resulted in a very high pitched sound (due to the very low electrical resistance of metal) which was almost painful, as it wasn’t until later that I added some tuning to make a maximum frequency to avoid extreme audio annoyance. In the third row, the kids went into the kitchen where the cooks were preparing lunch for the school. They listened to the hot metal pot as the cooks warned them to be careful and not get burned. They then asked if they could listen to some food and the cooks curiously engaged offering food scraps and listening in. The fourth, fifth and sixth rows show people playing with their bodies as part of the circuit. In the fourth row, on the left a student touches the wires to my forehead then in the middle picture to his own forehead. In the fifth row, they touch the wires to their faces and on the right play hand clap games in a circle. In the sixth row of images, the student touches the wire to his face and either due to a capaciting charging effect or because he was adding more pressure to the wires with time the pitch of the sound went slowly up and up and up and he felt that he was being charged up or transformed into another being. So he started dancing in a Michael Jackson style perhaps it was the Thriller dance as if he was a monster. He can be seen howling in the picture on the left. In the seventh row, the Drishya school facilitators took an interest in what we were doing and began to explore the electrical resistance of the edible garden. Compared with the PicoCricket version of this resistance-to-sound conversion circuit, this circuit was so much louder (bigger speaker, bigger voltage), with such instantaneous feedback (analog .1ms delay instead of digital 100ms delay), and measured over so much of a wide range of resistance (10K to 100M instead of 10K to 1M) that it instantly caught everyone’s intrigue: from me, to the Drishya students, to the Drishya mentors, and the graduate design school students and teachers at Srishti where we ran workshops on replicating the circuit:

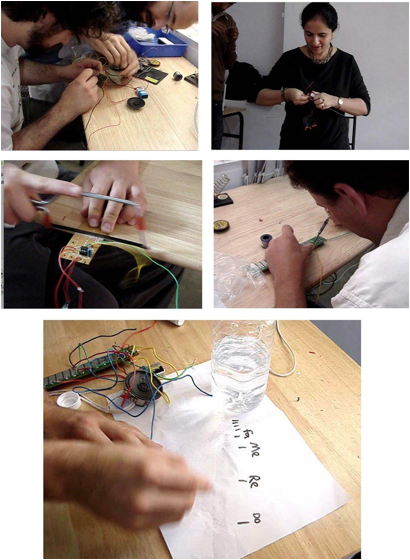

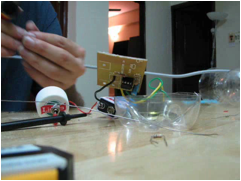

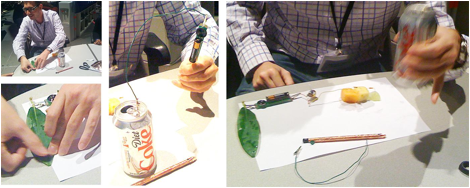

Figure 5.18. Top Left: Zack Denfeld, a professor at Srishti, assembles his circuit as I look over. Top Right: Teacher from K-12 school and a collaborator of ours from the Media Lab assembles her circuit. Bottom Left: Hacksawing the circuit apart to remove the “piano” part so that the world can become the piano. Bottom Right: Gabriel Harp solders his circuit together in the “World as Musical Instrument” workshop. Bottom: I pour water on a piece of paper after the “World as Musical Instrument” workshop and for the first time ever experience the joys of playing water as a musical instrument. I start to label the different points at which pitches on the major scale can be heard. Note at this point I am still touching two wires to the paper, not using my body yet. Bottom image is a still frame taken from a video by Dipti Sonawane.In what was basically an amazing coincidence I walked into Zack Denfeld’s classroom as he was teaching design grad students about circuit hacking. I showed the simple sound-making circuit in the ziplock bag and we played with water globbed up on a table. When you put water on a waterproof surface, it tends to glob up and stick to itself due to its own hydrogen bonding through what is termed water cohesion. But when you touch water with an object or your finger, the water also tends to stick to the object, termed adhesion. Through this cohesion and adhesion, simply playing with water on a waterproof surface is really interesting. But when you add a sound dimension to listen to the shape and connections of the water as they move around on the table, it was mesmerizing for the group as well as for myself. We decided to hold a workshop the next day for people to make their own circuits. I made a special run back to S.P. Road (Figure 5.13) to get the electronics ready for the workshop. Note that every driving excursion involves a driver who drives the car for you and what could almost be called a fight or perhaps on a good day a dance with the other cars, the heat, etc. The next day we all made our own sound-making circuits as depicted above in Figure 5.18. The next night I made a “Curious Caterpillar” out of the hacked harmonium circuit by copying a page in the Bangalore kids’ playbook and repurposing a plastic bottle, adding a switch into the nose and sparkly pipe cleaners onto the antennae wires. I added a neckstrap reusing my lanyard to help with hands-free operation.

Figure 5.19. Me soldering on the kitchen tableThis was all the most advanced “product design” I had ever done at this point with circuit and casing integration.

Figure 5.20. A repurposed plastic bottle containing the “Harmonium Circuit.” A lanyard is attached for hands-free operation. The nose is a switch. The googly eyes are added just for personification. And the two wires to explore the world are positioned as if they are the bug’s antennae.

Figure 5.21. The Drishya facilitator made his own circuit as well the following night. The picture on the bottom is while the electricity was out. The man on the right is the cook, the man on the left is a Drishya facilitator and on the left in the bottom picture is a Drishya student.Now the facilitators were interested in getting in on making their own circuits. One of them stayed late after classes, which was a significant sacrifice, and we worked with intermittent electricity and ungrounded electricity as I learned by getting my first A/C high voltage shock. They all laughed at me (in good humor). The cook also stayed and one of the students soldering with us into the night and having a great time. The experience was an adventure, and the enthusiasm for exploring electrical resistance in the world as a sound was surprisingly high, though no one knew where it would lead. The Making of an Invention Kit at MIT Returning home to Boston, I showed this circuit to everyone both in my research group and to friends and collaborators. In discussing with Jeff Lieberman, he showed me that you can draw with a pencil on a piece of paper and that is conductive. We pressed the two antennae against the graphite “circuit trace” on the page and moved them closer together and farther apart to listen to the changing sound. That was interesting. Crayola was coming for a visit to the lab as a sponsor, and the night before, as I sat meditating, I realized that the circuit should not be separate from the pencil, it should be connected to the pencil as a backpack. I got some perf board and soldered together the most compact version of the circuit that I could, copying the layout from a classic 555 astable timer circuit diagram freely available many places online.

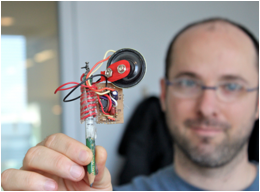

Figure 5.22. Me holding the original Drawdio pencil with a small screw jacked into the graphite at the topThis model (depicted in Figure 5.22) still required a wire to wrap around and touch the page, but when we presented it to Crayola I also presented a second model that allowed you to use your body as the wire so you could just touch the page with your finger. It wasn’t until later that that circuit was fine tuned and worked well with the human body. At this point I sketched out a circuit to etch on the Modela milling machine on foam backed copper (FR4)

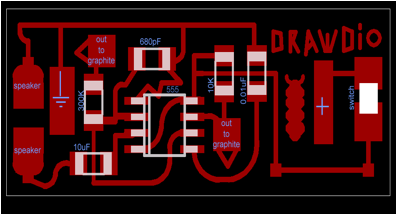

Figure 5.23. Eagle Board file showing the traces for the first custom-milled Drawdio circuit. You can see the caterpillar drawing left over from before the board got the name Drawdio.The name of the circuit evolved slowly from Curious Caterpillar, named after the bottle form factor with the antennae, to Drawdio, named after “Draw + Audio” in the pencil form factor. I started to iterate on designs

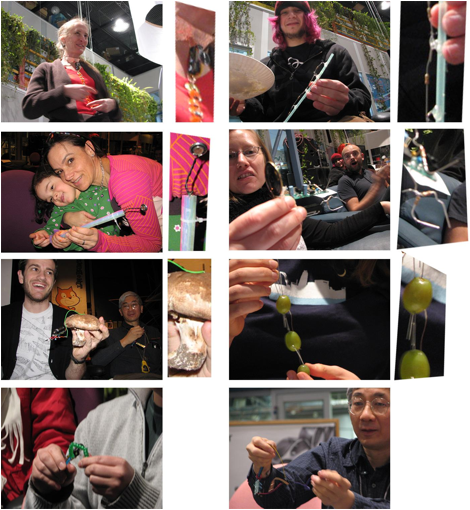

Figure 5.24. Mechanical pencil with Modela-milled Drawdio circuit attached. The mechanical pencil had the attachment to the metal tip of the pencil which came into contact with the graphite as opposed to the screw into the top of the pencil.I took this mechanical pencil to my first ever Maker Faire in Austin (the second year Maker Faire had existed). I let many people try it out

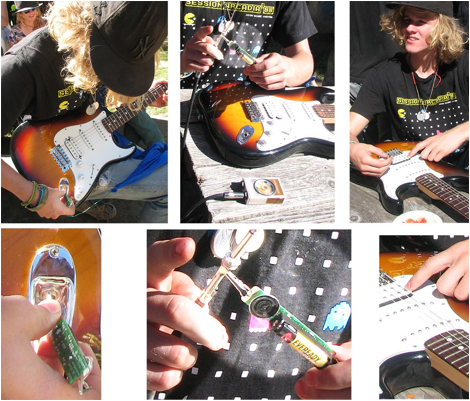

Figure 5.25. Youth trying mechanical pencil Drawdio at Austin Maker FaireAt this point Maker Faire was relatively unknown around Media Lab and several in my group were indifferent to me mentioning I would attend. (Thanks to Amon Millner for taking me). There was so much enthusiasm for Making in general at Maker Faire, as well as that expressed for the Drawdio pencil. I met up with Limor Fried who I knew briefly from MIT who now runs Adafruit, an electronic kit making company. She said Drawdio would make a good kit. Back at MIT Media Lab I continued to invent using the guts in the circuit of Drawdio.

Figure 5.26. Left: a musical jacket with the Drawdio circuit inside “Ok2Touch”. Right: a musical paintbrush with the Drawdio circuit inside exhibited in museumsI then got back in touch with Limor Fried and Phillip Torrone, the two people in charge, at Adafruit and we agreed to make a Drawdio Kit together. This would be a solder-it-together type kit and then attach it to a pencil to make a Drawdio. At this point I started to realize that I was inventing all kinds of fun stuff with this circuit and that the real product here wasn’t the pencil, but the ability for people to invent all kinds of things, just like I had been doing, they could do it themselves. I suddenly saw that this was where the real value was. Not a huge surprise since I was in a group, Lifelong Kindergarten, that studied creative platforms, but I had veered off into a separate exploration as a media artist, and now I brought the Drawdio back to the point of an invention kit. I released the kit with Adafruit and this gave me a steady supply of Drawdios to workshop with people en masse. I began to workshop the Drawdio (more on that in Chapter 7). I also created the “Sample Space” video which showed the Drawdio being used in 26 different scenarios within 1 minute and 44 seconds which garnered 630,000 views on YouTube. More on that video in a future chapter. The sample space video was probably inspired by Hiroshi Ishii’s students’ videos, such as Hayes Raffle’s Topobo video and in particular Kimiko Ryokai’s I/O Brush video. The original Adafruit Drawdio kit shipped with a pencil and a thumb tack and was intended to be made into a musical pencil. Note the innovation which came from Limor to jack into the graphite with a thumbtack through the side of the pencil instead of the screw through the back of the pencil.

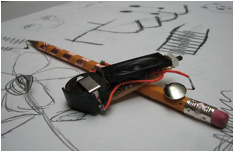

Figure 5.27. a Drawdio circuit thumb tacked onto a regular wooden pencil along with example of musical instruments drawn on the paper.

Figure 5.28. a cartoon depicting the flow of electricity when using a Drawdio Pencil: out one side of the circuit, across the outside of the skin of the body, through the graphite on the paper, into the pencil’s graphite core, and back into the other side of the circuit.This iconic project exemplifies one of the core principles of Drawdio usage: you can take an object designated for one purpose and reassign its intended use. Graphite can be a wire, drawings can be musical instruments, your body can be part of the circuit. Since then, people have invented hundreds of interactive objects using Drawdio as an invention platform. Furthermore, because the circuit is so simple, tens of thousands of kids have now learned to solder using their own Drawdio circuit boards from a kit.

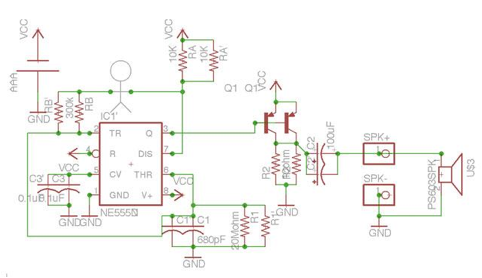

Figure 5.29. A modern version of the Drawdio Circuit, which consists primarily of a class of timers commonly called 555 Timers along with some peripherals such as a battery and speaker. The main difference between this 555-class Timer circuit and a typical one is that one of the resistors is left open “to the world." This is represented in the diagram by a stick figure. This is the version of the circuit that is currently distributed as a kit. This circuit design was led by Limor Fried with me giving feedback along the way. This circuit diagram drawn by Limor Fried.Because of the new insight that Drawdio is truly an invention platform, Adafruit and I released a second kit called Drawdio Fun Pack, which comes pre-soldered and ready to be used for invention:

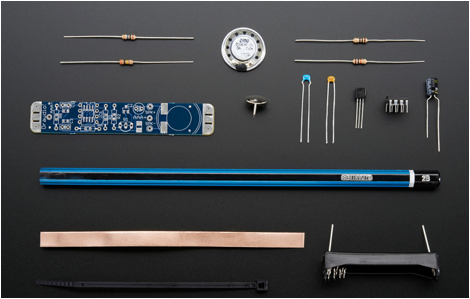

Figure 5.30. Drawdio Fun Pack comes with● Assembled & tested Drawdio - no soldering required!● Large brush● Soft lead pencil + thumbtack● 2 x Alligator clips● 4 x Wire ties (the photo shows 2, but the kit has 4)● 12" of copper tape● 2 AAA batteries included!This Image reproduced from adafruit.com. Thanks to Limor Fried for leading the design of this kit.This is the Drawdio that was used for all the workshops, and is the Drawdio referred to whenever “Drawdio” is referred to abstractly in the case studies below. Along with the kit there was also a Drawdio video which showed example projects that you might make with the Drawdio. This is critical to the activity. The original Drawdio actually isn’t that much different from a 40-year-old 555-timer circuit, just a couple alligator clips and circuit tweaks. But what is new and makes the product feel like so much more is possible is the Sample Project Space video.

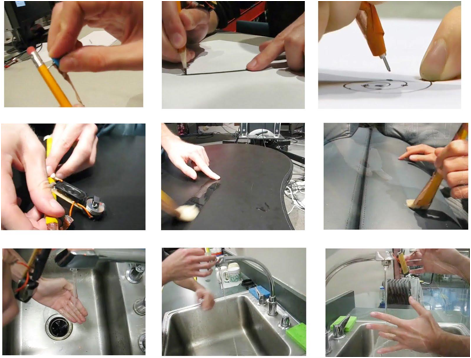

Figure 5.31. Introductory Portion of Drawdio Sample Space Video available for viewing at Drawdio.comMost workshops were run in conjunction with this video so it is important to show it since without it one might think “what do I do with this Drawdio thing?” This is the first half of the video where the viewer is oriented to what the Drawdio is. The first substantial scene is the Drawdio getting thumbtacked into the pencil as shown in the top row on the left. The pencil is considered the iconic example and also a great example of what you can do with a Drawdio. It’s also named for this example. Then the simplest thing is shown, a line is drawn and the finger touches the line and the pitch goes up and down corresponding to the finger sliding closer and further from the pencil tip. Then top row right a spiral piano is drawn and discrete notes are played by touching the pads with the pencil on the spiral piano, playing a tune. The circuit is then unhooked from the pencil and attached to an ordinary paintbrush, middle row left. Again a line of water is drawn, middle row center, and the finger plays the water as before. Finally a tune is played on a leather couch arm. The circuit is then unhooked from the paintbrush and attached to a kitchen sink, and again an up and down slide is played, and then a tune is played (in this case “The Itsy Bitsy Spider Went up the Water Spout”). In each of these three examples the circuit is built in front of the person and some orientation time is given followed by examples. This is the “slow” half of the video although it takes only a minute to go through these.

Figure 5.32. Second half of Drawdio Sample Space Video available for viewing at Drawdio.com.The video then speeds up and starts showing one example after the next in just a few seconds each. Top row is an indoor tree, a musical jacket, and a group holding hands. MIddle row is food: mac ‘n cheese, Gatorade, and a banana. Bottom row is outdoors, a tree, a metallic rock-like sculpture, and a bike wheel. At first they are about five seconds each, but they start to dip into the three and two seconds each range crescendoing until punk rock music plays and lots of images flash and spin. See the video at drawdio.com. The intention is to first orient the viewer, and show the full buildup of the project to make the viewer feel at ease that it is easy to do. Then to show a small jump from the first example, a pencil, to a more complex example, a paintbrush. Then a bigger jump, a kitchen sink. Then just jumping all over exploring various things as fast as possible, giving the sense of the range of possibilities. Ideally, the participant in the workshop who watches this feels informed and inspired, but still feels like there’s lots of creative space, in face more than before watching the video, in all the space inbetween the examples shown, or with re-exploring examples that are shown or variations thereof. 6. MaKey MaKey Genesis In this chapter I’ll tell the stories of how I came to think of computers as crafts, and apps as something worth remixing just like popsicle sticks are glued together. These stories will form the soup in which you will perhaps be able to imagine how Makey Makey could have come about. Then I will tell all about the evolution of Makey Makey with special attention to the design of the user interface, ending with the launch of the project. Computer Crafting Computer Crafting is the name I have given to using computers just as if they were any other craft material: tape, play dough, paper clips. This is to treat the modern advanced machine of our day as just another piece in our prototypes or crafts. In summer of 2009 I found myself back in India running some more Scratch workshops, this time on mobile devices (keep in mind this is just barely pre-iphone still) supported by the work of John Maloney and the Scratch Team. The workshop I designed was based on an idea called Awareness Mapping, a theme co-developed with Karen Brennan (my groupmate), and executed with support from Zack Denfeld and Geetha Narayanan’s Drishya team and worked like this: We went out and took pictures of urban nature in the slums the children lived in.

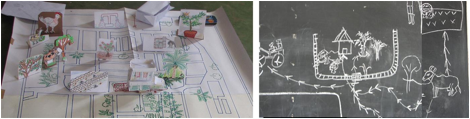

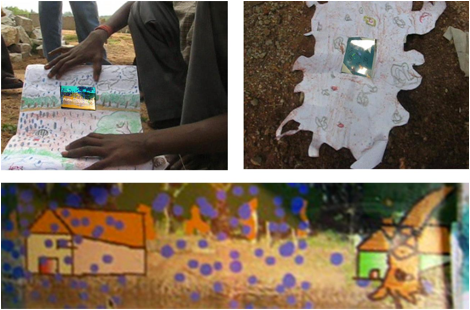

Figure 6.1. Students at Drishya, a slum school, “taking photos of nature” in their community however they choose to interpret that instruction.We drew a map on a big sheet of paper of the entire village. Each youth then picked their favorite example of nature, and we acted out what that piece of nature actually does with live role-playing theater. We then talked about how maps are static and flat, but actually the world is 3D, dynamic, and moving around. We drew a chalk diagram of parts of the map and added in arrows to represent the motion and dynamic nature of their village. Then we made 3D paper models to overlay on top of the map.

Figure. 6.2. Left. The map of the village with 3D popup models of each child’s favorite aspect of nature in their community overlayed. Right. A chalk drawing of one part of the village’s dynamic motion. The arrows show how the milk trade carries out each day.At that point it was time to make the map dynamic using computers as if they were just another craft material. At each part in the map where the children felt they wanted to represent an important part of nature to them, they cut a hole the size of the mobile device, in this case it was a Nokia 810. Then in Scratch the photos they took were used to create interactive projects that responded to taps, sounds, etc., and made some animations or noises as a result that represented the nature in that location. The resulting map had a dozen or so interactive mobile devices embedded in the paper that ran simultaneously.

Figure 6.3. Left. Computer crafting example closeup, screen worked into paper crafting. Right. Map with holes cut in it for mobile devices to be inserted. In the picture are myself, collaborator Zack Denfeld, and the Drishya students.The picture on the left is one of those 11x17 sheets of paper. It is a good example of computer crafting. The screen is embedded into the middle of regular paper. The bricks on the screen are contiguous with the bricks drawn on the paper, as is the water in the ditch (blue on the paper, blue on the screen, although color in the photograph appears mismatched due to screen brightness). A mosquito flies around in the ditch between the bricks. These mosquitoes can carry malaria and are a problem in this ditch in this slum village, which is why the student chose to focus on the corresponding picture he had taken in Figure 6.1 on the left. When you “clap” the screen sends the mosquito away but it comes back.

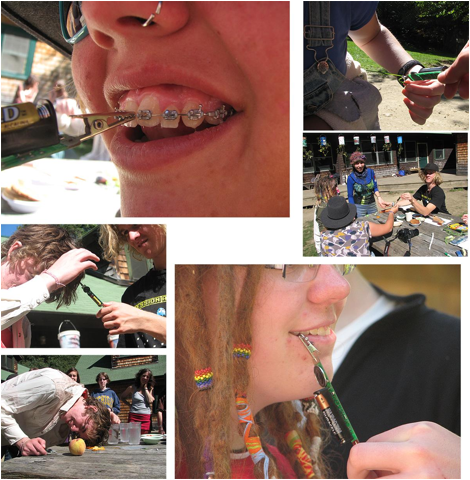

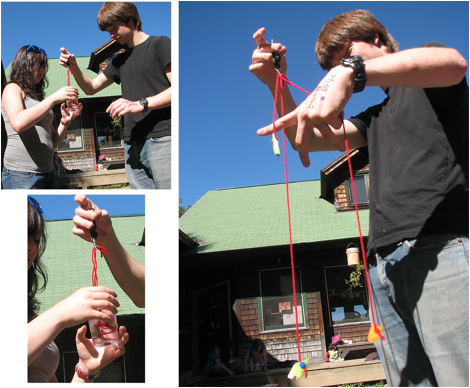

Figure 6.4. Top. Two examples of interactive map pieces being installed on site of the places in the map which they represent with computation and paper crafting merged. Left. A monsoon that ruined what used to be this student’s home. Right. A problematic bathroom/trash area. Bottom. A closeup on the screen of the monsoon rendering the student’s home unlivable (one of several frames of an interactive animation. In this frame the rain is the front layer that moves across the background layer of the houses and trees).After showing the map to the other students in the school, we also made individual installations for each location from the map, like little breakout interactive maps bits, and took them to the locations which the mini map represented. On the left we see an installation on the site of the student’s home which had previously been ruined due to a very heavy monsoon. On the right we see an installation on bathroom and garbage heap, where the paper itself has been made to blend in with the dirt and trash around it, as has the screen been made to blend into the paper. At each of these temporary installations the families of the children and some neighbors naturally gathered around the installation site as the children told their story of how they interpreted the interactive map and how the situation affected them. That Fall I continued my work on Computer Crafting using the Nokia 810’s in a Not Back to School Camp workshop where unschooled teens were explicitly encouraged to craft the mobile devices running an interactive Scratch project directly into their environments

Figure 6.5. Interactive Fashion - Scratch running on Nokia 810 duct taped into teen’s hat, at Not Back to School Camp computer crafting workshopAt this point I was so excited about the idea of crafting on the fly with computers the same way we craft on the fly with material (paper, popsicle sticks, and everything else), I decided to try out computer crafting for Halloween. I dressed up like a doctor, and I cut a hole in my blue scrub shirt near where my heart would be. I downloaded an animated GIF of a beating heart, and I loaded it into Scratch. I then made the speed of the rotating images be proportional to the amount of noise around me, so that the louder the environment the faster my heart appeared to beat, or if you yelled at me my heart would beat really fast. Then I inserted the laptop under my shirt. It was an IBM Thinkpad, which was able to open up to 180 degrees, so the trackpad was held tight under my belt while the screen was sticking way up to my chest over my heart where the hole in the shirt was. The keyboard sat hidden covered by my shirt, in between the hole in the shirt and my belt. All that was visible was the part of the screen showing the life-size heart beating, cropped by the circle cut in my shirt. I added a little fake blood to the T-Shirt around the hole, and carried around a knife with me that night saying I was doing my own open heart surgery.

Figure 6.6. A Halloween I made costume using a laptop inside of my shirt, a technique I call computer crafting.I knew computer crafting was going to be big, but I also knew that it had to be more accessible. Up until now, all the examples I have shown used custom software built (in Scratch) for that specific computer crafting scenario. It would be nice if apps could be grabbed and reused, with the customization being a later step. LEGO has one damn rule: you push blocks together to make them stick. That’s the kind of computer crafting we needed if we wanted a low bar to entry. Over the next several years I would try desperately to make something as complex as a computer controllable by something as commonplace as a pencil. Or as my advisor says in his paper, Computer as Paintbrush: “Which of these things doesn’t belong? Television. Computer. Paintbrush.” He goes on to say it’s the television that doesn’t belong. But when does a computer feel like a paintbrush? When does a computer feel like mud? I wanted to make that jump from drawing sounds with a Drawdio to “drawing” or “painting” computation with a computer. But how? I didn’t know. But I had lots of ideas. In this section I will tell about several prototypes that were never even named or documented, that took a day each, or a week in the case of Gesture Base Scripting. These ideas and prototypes are meant to show the space I was searching around in, which lead to a sort of area which I was steeped in when Eric and I first invented Makey Makey. Pencil Volume ControlAt first I got together with my undergraduate researcher, Tyler Williams, and tried using my trusty Scratch sensor board, hacked slightly to read higher resistance levels to make it more in line with measuring real world items. I hooked up a pencil to a Scratch Sensor Board, by jacking into the graphite running down the middle of the pencil using a thumbtack. I set up a program in Scratch to let the resistance of the sensor be linked to the volume of the music playing inside the Scratch program. In this way, I was able to draw on paper to change the volume of the music, and it was fun because I could draw different shapes and patterns that would control the volume in interesting ways: ● stripes that made the volume oscillate quickly between on and off over and over again as I slid the pencil across the stripes perpendicularly ● a simple line that slowly faded the volume up and down as I traced over it with the pencil ● Pencil sketched icons of a party, a restaurant, and a person sleeping, each of which would turn the volume to the appropriate loudness: max, middle, silent, when touched with the pencil (the amount of resistance, and thus the volume, was “programmed” by how dark the lines I drew to the icons were). This definitely felt right, but only being able to control volume just didn’t feel explosively expansive or empowering with wide scope. I experimented with controlling the mouse-x and mouse-y with the pencil and this was interesting as you could draw a mousepad of various shapes, so I explored mousepads some more next. Anything Mouse PadI had an idea to make a mouse pad out of a dish of water. I wrote a Scratch program to triangulate the 2D position of an object based on three distance measurements from the object each to a known separate point. I ran upstairs and grabbed Jamie Zigelbaum, a Media Lab student and collaborator, because prototyping alone just isn’t the same. We took a small plastic tub, actually coincidentally it’s the same one pictured in Figure 5.7 Left, and attached three wires to the corners of the tub on the inside with tape. We connected each of the wires to the resistance input sensors of the Scratch Board (hacked with 100M Ohm resistors so that it could sense the higher resistance of water accurately). We then grounded a fourth wire, and moved the fourth wire through the water in the tub. We used the Scratch program I had written earlier to transform the three resistance measurements into a location of the fourth wire, so that we could then move the mouse cursor on the Screen to wherever the fourth wire was in the water dish. Within 2 hours, after a lot of calibrating, everything seemed to be working, so we used the Scratch “pen down” feature to try to draw a line on the screen by drawing a line in the water. Then line ended up being jagged and a bit curved, but it did work! Momentary excitement faded into the big question: How can this be an empowering toolkit or platform that many people can create with? The idea of making a “mouse pad out of anything” was pretty interesting: mud, cereal, a still-wet painted picture, and to this day I wonder if there is something latent in this project waiting to be developed. But I was searching for something bigger. Something without: ● A long or potentially confusing calibration stage ● The need to use with special software ● More diverse outputs than different types of mice Gesture Based ScriptingNintendo Wii controllers (WiiMotes), which are basically bluetooth-enabled accelerometers for the purposes I’m using them here, had just become easy to hack with the release of some new open source software. Tyler Williams and I repurposed a Hidden Markov Model Gesture engine and combined it with a WiiMote and a scripting language that let you make your computer complete certain tasks (called scripts) upon receiving a particular gestural input from the WiiMote. Further we let you define your own gestures. So what we ended up with was a situation where you could define a script by recording it on your computer: press record, do an action with the mouse and keyboard, press stop. Then that action could be repeated when you perform a certain gesture. To define the gesture, hit record, move the WiiMote in a certain pattern, then hit stop. In this way you could make actions happen, discrete actions like pushing a button to initiate a sequence of events rather than tight feedback of each motion of the hand mapping to subtle shifts in sound or mouse motion. In this way you could make: ● A video play when you take a sip from a cup (WiiMote taped to cup) ● A sound play when you dance a certain dance move (WiiMote tucked in gym sock) ● An email send “someone is here” when someone opens your door ● Make a character in a game jump when you jump For the first time I felt the power of being able to control every webpage and every computer program on your computer. The scripting language worked just like the mouse and keyboard, so anything the mouse and keyboard could do the scripting language could do. This was so powerful because nearly every piece of software ever made can be controlled by mouse and keyboard. However, configuration was still very time consuming, the gesture recognition could be frustrating, and didn’t always work. In addition, scripting languages are complicated and only execute correctly if you set up all the right conditions. With enough work, this has a chance at being a powerful platform, but I left it as I felt its fruit was not low hanging enough from an implementability standpoint, and something felt a little bit too Artificial Intelligence about it instead of Human Intelligence. In other words there was a feeling of wiz bang about what the computer was doing, when that type of feeling should really be felt by the person for what they have created. In any case I still believe it has a chance of going somewhere someday.

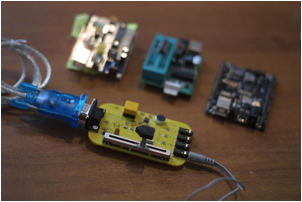

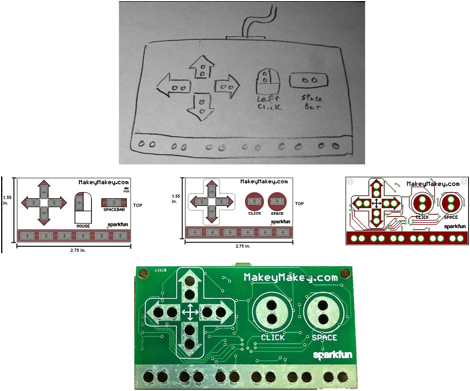

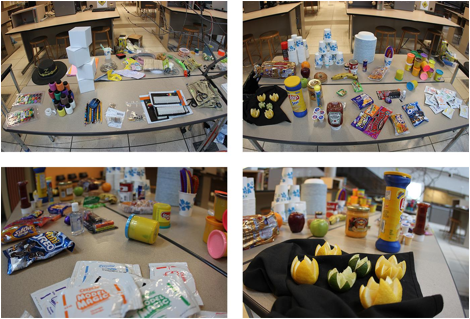

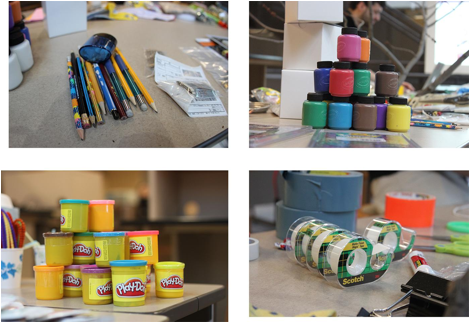

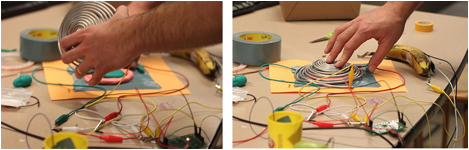

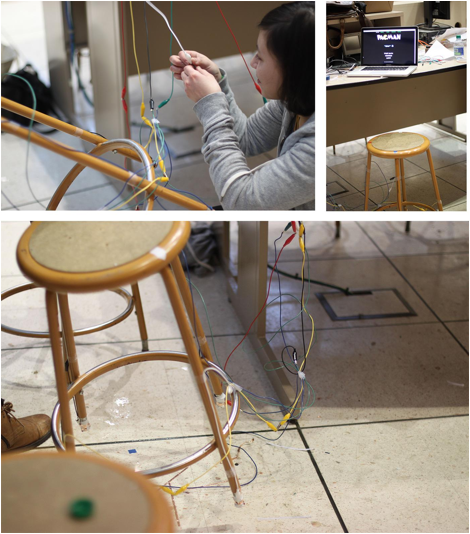

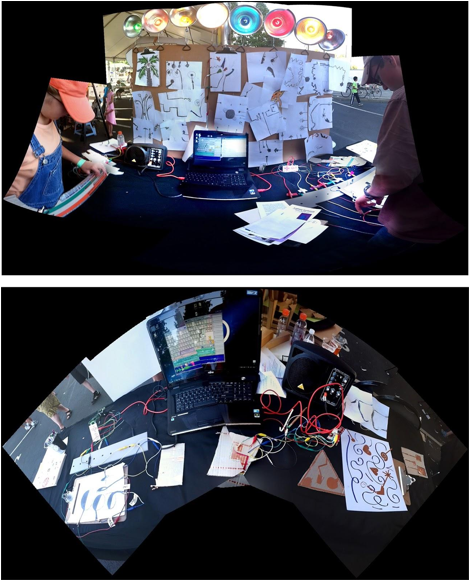

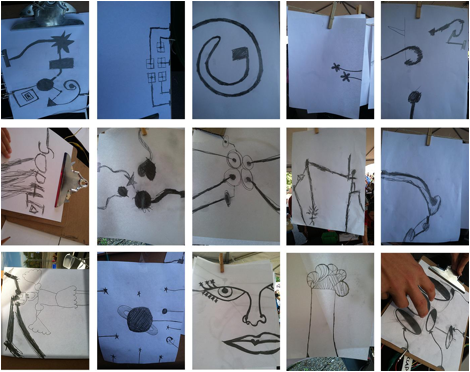

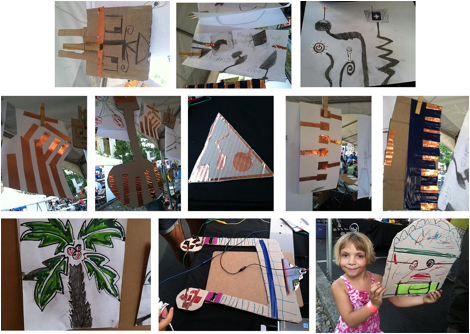

Application Dumpster DivingThis would allow a new form of digital repurposing, or what I sometimes like to call digital dumpster diving. By allowing people to scrounge around the web for photos and sounds, many visual and sound artists are greatly empowered with the entire digital world’s worth of billions of images and sounds to pull from. Photoshop and Audacity are examples of image and sound editing programs that let you chop up images and sounds that you find and remix them in new ways. Currently, only the coding elite, people who have a mastery of programming, can mix and match pieces of applications (typically in the form of code) to make new uses out of the applications. How close can we get to giving the non-expert-coder the opportunity to grab apps and use them in new ways, to dumpster dive through a pile of interactive webpages, and make new meaning out of what they find, just like an artist who pulls items from a dumpster and makes a sculpture? Probably not as close a coding will get us, but by giving people the ability to control and use applications in a new way, that is a step closer with a lower bar. What if we could extend applications to the list of things that can be found and reused on the computer and on the internet? Magic Seth first introduced me to a new type of workshop [Cottam, Defcon 2013, Sketchtools: Prototyping Physical Interfaces] and hacking activity where people take keyboards, pop the plastic keys off and solder wires to the two leads underneath the button, which would normally be connected via a person pushing the keyboard button. Now the two leads could be extended to two wires which could be taken out to the world and hooked up to any ordinary button or switch, or one can make a custom switch by which two pieces of metal come together through any action, thus connecting the keyboard button circuit. This idea was powerful and reminded me of the scripting I had done in the gesture-based scripting section and of the mouse input I had done in Anything Mouse Pad section. Eric Rosenbaum started using this technique to trigger the pieces of software he had written using big buttons rather than using the laptop on which he had written the software. You see, a big secret of prototyping is that the fastest way to prototype anything is almost always on a laptop (in other words, on a personal computer) because that’s where coders have the most freedom with multiple powerful languages and powerful processors all available in the same place. But unless your software is meant to be distributed on a computer, then you quickly want to embed that computer into your creation so it becomes more experiential and less like the experience of using a computer, or you want to migrate it to a new embedded platform that is ready to talk to sensors. Here Eric and I were, literally stuffing an interactive music project Eric had made on a laptop into a box. This meant stuffing the entire laptop into a wooden box, and then popping off a mouse click button (analogous to how the people would pop off the keyboard keys in the workshop mentioned above), and soldering wires to the mouse click internal leads to hook up a big red button on the outside of the box which would help control the interactive sound installation. If this is not computer crafting then I don’t know what is, but it requires a somewhat high level of hacking skills to write the custom code, and solder to the mouse guts. At this point a new idea was fertile and ready to emerge. We needed to give people access to push any keyboard key or control any mouse function, just like the hackers in the workshop, but on the fly in a matter of seconds. This could be the secret “duct tape” that could join any computer app with any everyday object. Inspired by computer crafting, and app dumpster diving, and still interested in “how to make Drawdio talk to computers,” Eric Rosenbaum and I built a prototype of what yet had no name, and would have interim names like Project Q and The Mousinator, but would become Makey Makey. Eric carried out the first prototype building with some technical hardware input from me for a workshop stint at the Exploratorium. This first prototype looked like this.